The issue of energy in a mining country

Jean Katambayi in Congoville

"What will we do if history repeats itself? I console myself by showcasing facets of my own world as possible avenues of thought in my work." Artist Jean Katambayi explains his views on this topic with Middelheim Museum curator Pieter Boons.

A non-proportional condition

Pieter Boons: According to Sandrine Colard’s concept, Congoville represents the dense urban layer that results from the colonial history in Belgium: its buildings, monuments, imperial myths, and its Africandescendant population. To what extent is your work related to the concept of Congoville?

Jean Katambayi: MM, the work I show in Middelheim Museum, is related to the Congoville concept in a very broad sense. The ideas behind this work show a country faced with a non-proportional condition towards time and towards its own sovereignty. The (historical) extraction of minerals in my region keeps on taking place and keeps on spreading its political, economic, and social ‘mist’ over the country.

In her essay Sandine Colard speaks about “unlearning an imperial mindset”. What can this mean to you?

For me, unlearning imperialism can start with facing the pain of our nation’s ongoing struggles. Instead of finding ways to flourish, the Congolese people are being confronted with the opposite: Every day they get stuck more and more in uncertainty. Strangely enough, modernity and globalization presented new evolutional methods for societies in the last century, but until today they remain intangible for the Congo’s inhabitants.

An autobiography raising questions

Can you share with us the visual representation (or an image) of the concept of Congoville?

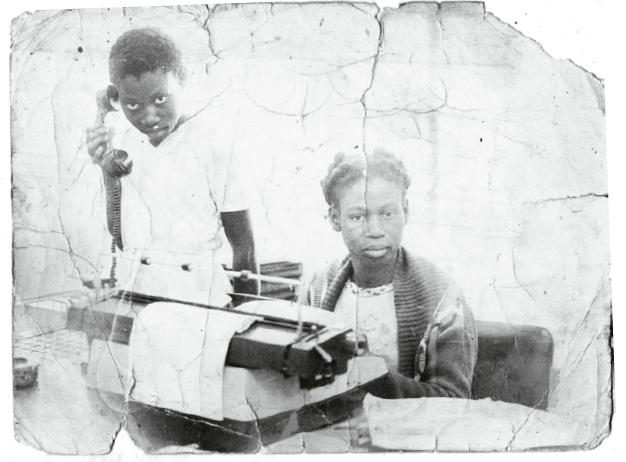

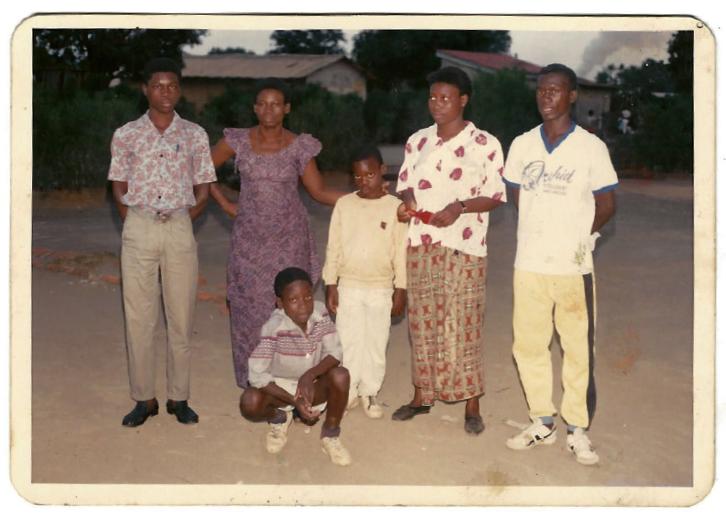

I selected two images from my family archive, as my intervention in the Middelheim Museum is an autobiography, raising nostalgic and at the same time retro-futuristic questions. Could we imagine the trigger of our society’s evolution? What will we do if the same history repeats itself?

Waiting for an answer, I console myself by showing elements of my own world as forms of thoughts in my work. The house symbolizes the universe of the mine workers, while the lamp refers to the extraction of minerals and energy.

In the black and white image you see my mother (Manyonga) typing in her Gécamines office while my sister (Musau) is on the phone. The family picture in color dates from Christmas 1990, and in the background there is the chimney of the Gécamines factory spreading its smoke. The factory was surprisingly still working at that time. We are standing in front of our house; I stand the first from left next to my mother.

Different coexisting approaches

What are the ideas behind the works you show in Congoville?

The work MM, is part of my general body of thought relating to industry, colonialism, employment, urban planning, and the future. MM teaches us that the world can contain a lot of different approaches that can coexist all together. Their differences will remain, as this is what makes them unique; on the contrary, their commonalities will enhance other forms of endless reconstruction of reality.

This work shows the opposite regression between postcolonial times and the present reality in the Congo: the absence of electricity as a modern and universal energy. Speaking about this message, I can imagine my work has a strong emotional impact on the audience. And as I encounter that all of the artists have strong messages, I hope this exhibition as a whole will continue to live in the imagination of the visitors.

Open air

How does the context of this exhibition open up the work or influence its meaning?

The Middelheim Museum is primarily a museum open to the sky, which is an important parameter when perceiving this work. This specific condition allows the work to entangle with other outdoor works, from the Congoville exhibition or from the permanent museum’s outdoor collection presentation. The openair aspect is a very determinative element in conceiving the work for an artist, and it also evokes the question in how the work can be mentally ‘open’.

So the consequences of working under the open sky creates a lot of possibilities for the artist and for the spectator. The interpretation of my work in this exhibition, but also in general, is taking its place in the current debate of decolonization. It always plays with a multitude of questions and perspectives on strategies that deal with our shared heritage and history.

To what thinking or writing is your work related, and why?

As a joke I was going to say the Bible to emphasize its importance within a broader African thinking. Many Africans use it as a refuge, looking for answers to justify the stigmatization of colonialism.

On the other hand and completely opposite to the Bible, the quote from the French chemist Antoine Lavoisier inspires me a lot: “Nothing is lost, nothing is gained, and everything is transformed.” This quote confirms to me that life is just a conjunction of approaches.

Interaction of energy flows

How do you engage with art as a possible strategy for healing?

This is a very good question. To me, society is an interaction of energy flows. The quantities of energies are very much connected with the qualities of energies. My commitment is double: to play on the quality and the quantity of energy. In doing so, I try to maintain the most important molecule of our cosmos. I imagine that ‘the molecule of healing’ is empowered through my works to a capability of crossing the most resistant planes.

Which book do you suggest to read within the context of your work in this exhibition?

Louis Figuier, Les nouvelles conquêtes de la science (Paris: La Librairie Illustrée, 1886).

Middelheim Museum Curator Pieter Boons in conversation with Jean Katambayi.

This text also appears in the publication accompanying the exhibition.

About Jean Katambayi

Jean Katambayi was born in 1974 in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. He lives and works in Lubumbashi, DRC. Trained as an electrician, his entire artistic practice is imbued with his fascination for mathematics, engineering, geometry, and technology.

Profoundly marked by his upbringing in the workers’ camp of his mining hometown and by its mechanization, Katambayi creates fragile and complex installations and drawings inspired by sophisticated electrical circuits and technological studies. His works are part of a search for solutions to social problems in current Congolese society, as well as to the country’s depletion of its enormous energetic resources.

Often made of recycled and impermanent material, such as cardboard and recycled electronic material, the artist’s poetic pieces attempt to redress the imbalance of the world’s hemispheres.

Exhibitions

Jean Katambayi has had numerous solo shows (Trampoline Gallery, Antwerp; Stroom, The Hague; and more) and group exhibitions:

- Palais de Tokyo, Paris

- Dak’art, Havana, and Lubumbashi biennales

- Museum für Völkerkunde, Hamburg

Among other places, he has been in residency at the École Supérieure d’Art d’Aix-en-Provence (Aix-en-Provence, France), at WIELS (Brussels,), and at the Visual Arts Network for South Africa (Johannesburg). His work is part of the collection of Muhka (Antwerp) and Mu.Zee (Ostend, Belgium).

Lately Katambayi has been participating in the ongoing On-Trade-Off research project, a collaboration between Enough Room for Space (Belgium) and Picha (DRC).