Turning sand drawings into 3D structures

A conversation with Kiluanji Kia Henda

Kiluanji Kia Henda (1979, Angola) creates architectural steel sculptures inspired by traditional sand drawings of the Chokwe people. The sculptures and performance take on a unique new significance in COME CLOSER. Curator Pieter Boons engaged in conversation with the artist.

The impact of travelling

What is the origin of your artist practice? Where did it all start?

In the very beginning, I wanted to become a musician, although my band never went really far. But before that I got the opportunity to live in South Africa where I had theatre classes. When I returned to Luanda I met some visual artists. I was jealous of their independence when producing their work. In music or theatre you perform in collectives, which is more complex.

The interaction with the visual artists from downtown Luanda reminded me to my teenage years where I had an interest in photography, like my brother who had his own small photo laboratory at home where he printed his photos. I decided to work with image.

So since the beginning I was interested in different disciplines. I prefer to deal with the variety of disciplines, and how to use them for the stories I want to tell, instead of becoming a specialist in just one discipline. It also had a lot to do with my personal story, my continous travelling, being in different contexts, which have a big influence on my artist practice.

You travel around the world, and work in different countries. Is it a deliberate choice? How is it, being all over the place?

This travelling was necessary in my thirties – I’m 44 now – to become an international artist. Angola doesn’t have a strong art scene, so it was vital to my career to develop an international network. Until 2016, I spent almost 8 years years without having my own home. I lived in different places for 3 to 6 months.

This had a severe impact on my practice. I’m not that kind of artist who produces in a studio, dealing with research and traumas. In my approach, the interaction with the context where I create becomes very important. This brought me to a different understanding of the road, of my own life, my fragilities, but it also made me aware of the strength that I had to carry on.

Since 2016 I have my own house in Luanda, close to my family and friends. I’m happy to live there. So the travelling changed. I have Lisbon as a second basis, where I do a lot of production.

I’m also aware of the limitations in Luanda. The social context and economical situation create several limitations. But many of the topics I want to explore as an artist are very connected with oral history, in Africa in general and in Angola specifically. So I feel that need to spend time there. I don’t want to fall in the risk of working into narratives, working from a distance into some specific reality. For me it’s important to not loose the connection with this reality in Angola.

Home base in Luanda

It’s a way to ground the works you make, in their specific context. I can also imagine that, as Angola doens’t have a huge art scene, you have to remain visible there.

It’s a kind of a commitment to the community in Luanda. At the same time, the government doesn’t provide you any minimum support. There’s a total absence of the state. So when artists have some succes, they can feel this obligation of sharing it with the artistic community. As an act of generosity, I’m very opened to do that idea, but there’s also a lack of protesting against this passive government attitude. We cannot just take the responsability of what the government should do.

I think being a good artist, good in what he does, should be enough for what an artist is meant to be. But these days the artists need to be entrepreneurs as well … I do it too, but I feel a need to be balanced. We should also demand more from the artistic community in Angola, to put more pressure on the visions of the ones who have the power, and wake them up.

Exploring boundaries in COME CLOSER

Let’s talk about the exhibition. COME CLOSER explores the boundaries between performance and sculpture. Performance has blurred the three different roles in experiencing art: traditionally an artist makes an artwork for an audience. But performance at a certain point questions the artwork by making things that disappear when the performance is finished, or by inviting people from the audience to make it together with the artist. Sometimes the artist is present and gives the score, sometimes he’s absent. In your work you question boundaries as well, f.i. by inviting the construction people to become performers, or to consider the construction as a performative act.

I do agree my work is an exploration of boundaries. The act of bringing an artwork to life becomes performative many times. Some ordinary, daily life repetitions become a performative act in many senses.

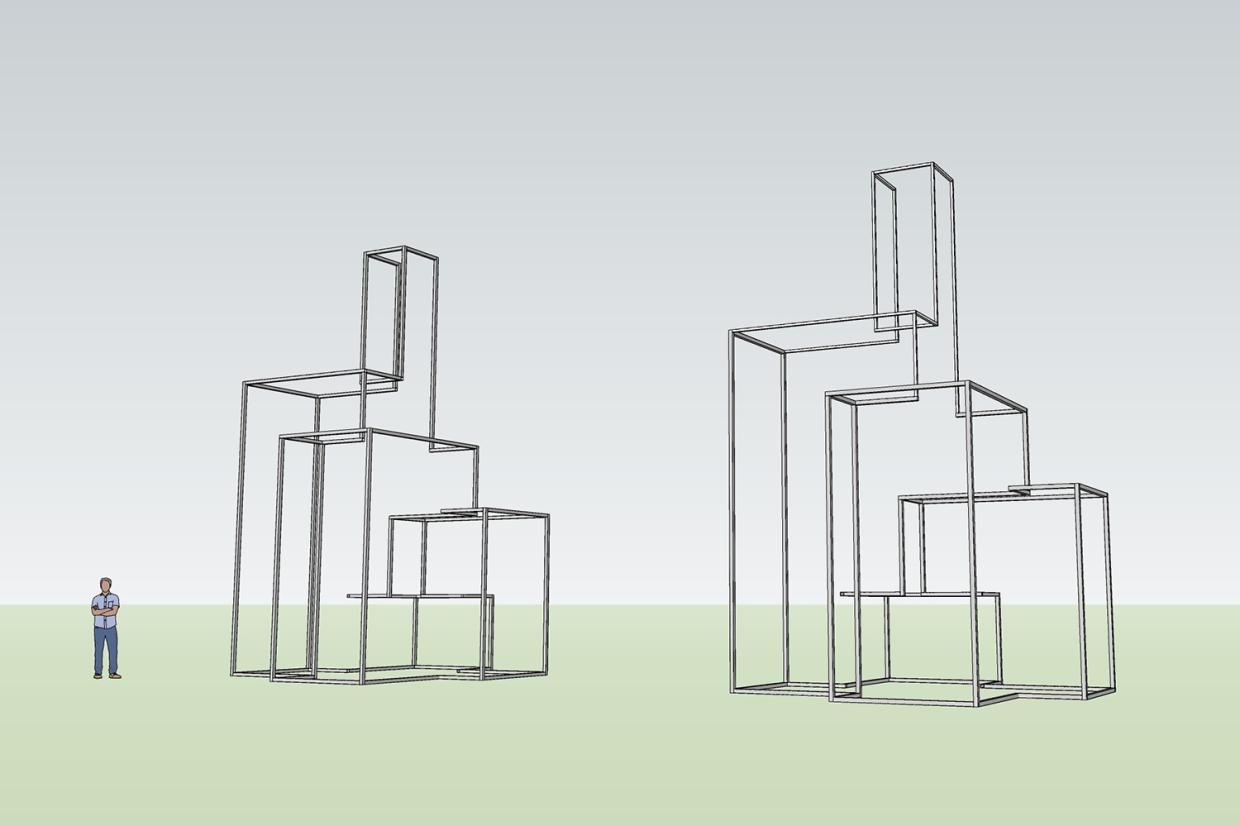

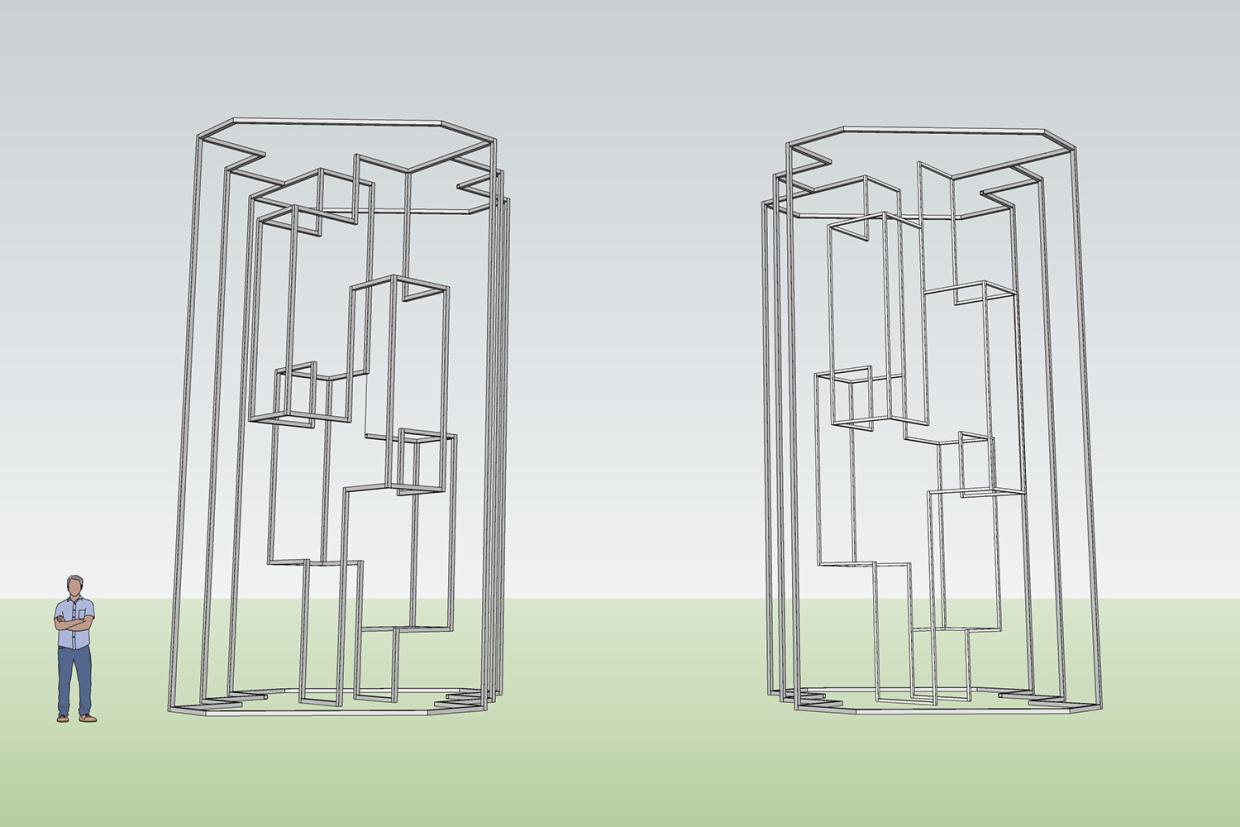

I’m using the sand drawings from the Chokwe community, made by storytellers. They draw them in the sand while telling a story. What we’re doing is turning that drawing into a 3D structure. To me, the act of building is much the same as drawing it. This act is connected with the performance, with the story that is being told. So for me it really makes sense to have the construction workers as part of it.

In your performance you try to look beyond the point of a sculpture as a finished static object. There’s a comparison with the sand drawings, because the act of drawing and telling the story is more important than the final drawing.

The drawings are similar: they are all fragile. People draw them in the sand and afterwards erase them. So the drawing is not preserved for a lifetime, it’s all ephemeral. It’s not about the drawing but about the story being told, the passage of knowledge.

In my work it’s different because we turn the drawing into a 3D object, a solid sculpture. It’s a longer process that begins really performative. This aspect is very important to me because what the audience is brought to is many times a finished object. Here we can play with both: the creation and the finished object. As an artist I really enjoy the process of making it. That’s the closest connection I can have with an artwork: after the work is created, it goes to a different dimension that I cannot control anymore. It doesnt’t belong to me anymore.

So you’re opening up the creation process. Do you agree that it’s getting others involved in the work, and that the performance is giving them agency?

It does. Somehow you’ll always have an idea of the different stages of the work. It’s different when we see something that is already finished, or look at something that is being created in front of you. It creates a different relation with the artwork when they see it coming to life. It also plays with expectations. When you see an artwork being done in front of you, you create an image in your head of what the possible outcomes of the work could be.

The collective participation on my process creation is very relevant, I am always opened to be influenced by other people´s ideas. It’s all about the diaglogue and team work. The musicians, the architect, the performer, their opinion is highly important to define the directions on what then becomes the final artwork.

Uncomfortable stories

We haven’t talked about the story yet. I’m very interested to hear what stories the storyteller is telling us in the work.

There are two central aspects. The first is, I’m working with these drawings from the Chokwe people. This ethnic group is from the east of Angola, in southwestern parts of the Congo and in Zambia. So it’s a big former kingdom with huge cultural heritage. But this kingdom is located in an area of conflict since the beginning of the 20th century during the Portuguese colonization, because in this region you have the biggest diamond mines in Africa, which led us to the “blood diamonds” conflicts. I see a strong connection there with Antwerp, famous for trading diamonds.

The exploitation of diamonds is a story of colonisation by European countries in the beginning of the 20th century. The original Chokwe drawings are now part of a tradition that no longer exists, because of the brutal process of colonisation. They were very important as a way of resisting the colonial domination. It was also a way to preserve the culture and to pass it to generations. Telling stories was a way to preserve the knowledge and culture. So these drawings transformed now to sculptures, with these dimensions, here in Antwerp, are for me also a kind of manifest of resistance. It’s giving continuation to the importance of the drawings.

A kind of resistance

These sculptures come in a series. You’ve been producing them over more than 10 years. They have been on display in London, in Europe, in Sharjah … Is that the common line that connects all these sculptures; monumentalizing a way of resistance?

When working in Sharjah, the third-most populous city in the United Arab Emirates, my work was more related to the urbanisation phenomenon. I was intrigued about this process of building a city in the desert, which was much what was happening in Dubai that time, in 2014. Some 70 percent of the buildings that were being constructed were empty.

So I used the drawings to create those empty structures in the desert. By then I was much more concerned about the ephemeral aspect of those drawings, and how I could use this to talk about the process of entropy. I wanted to tell the story about the birth, the life and the death of a city.

Those structures were representing an idea of skeletons of buildings, like ruins. Because nothing is more similar to ruins than a building being constructed. It has a different meaning maybe, but it still has the connection with the ephemeral. From that series I did a multi-channel video film which was telling the story of a man in the desert and his attempts of conquering the desert. This film was based in 4 different performances in the desert. We inserted twelve iron bars into the soil of the desert against clockwise movement, built a wall in the desert, we made a bleeding dune… All these performances became a film.

It’s similar to what you do in COME CLOSER, but you're telling a different story now.

That's right.

It shows how the place I’m working in has a strong impact on my creation. This interaction is important for me. The structures shown in this exhibition in Antwerp became even stronger than what I did in Sharjah, because it has a direct impact on what those regions in Angola are living today. The harmful of the diamond exploitation, not only during the colonial times but also after independence ...

When we come to discussions about colonial influence, we often limit ourselves to the period before independence, even if we are aware of new colonial strategies. But the diamond business and the commercialisation is still affecting our country today. So there’s another kind of reparation that should be discussed. Not just about what happened during the colonial time, but also what happens now.

The provinces of Lunda in the east of Angola became like a huge hole. All the cultural traditions from sculpture to drawing to paintings, disappeared in a very violent way. It’s really tragic what happens in that region. And this is all connected to the fact that it’s a region rich in diamonds. So it’s an important opportunity to talk about the cultural importance of that region, mixing the storytelling tradition with reflections on the approach of the reality now.

New performance in COME CLOSER

So that’s also why the title of the performance (“While I dig into the darkness of the earth, I can see the bling of death in your eyes”) is making this link to artisanal mining. Is that correct?

Somehow, yes, although it also refers to industrial mining. They’re still digging that hole. But it’s much more connected to the artisanal one. It brings it to a more personal dimension. The title bears a strong image: normally children are used in artisanal mining, because they weigh so light. So they tie them to a rope and drop them inside the holes. It’s much easier to lift them.

But at the same time it’s monstruous. It’s also related to the fact artisanal mining during colonial time was forbidden for the owners of the land. If you would get caught by the colonial police with a diamond stone, you’d get in jail the same time as for murder. There were also people doing artisanal mining, that were getting hunted and shot from helicopters. It was brutal. So that’s the idea of the the deadly shine in the eyes, in the performance title.

The other sculptures have titles like “The Watchtower” and “The Palace of Crystal”? How did you decide upon these titles?

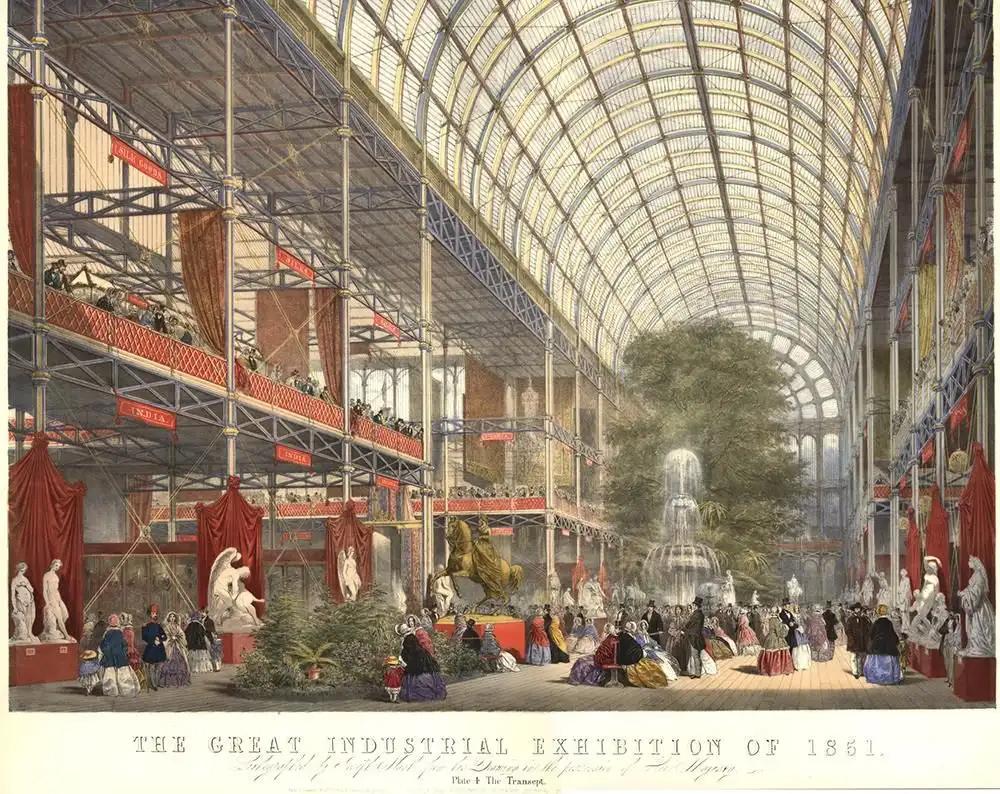

The real meanings of this drawings are “The Web” and “Charcoal Bank”. I chose “The Watchtower” because of the physionomy of the object itself. But there’s also an aspect about the system of power and domination. And “The Palace of Crystal” refers to colonial display in the famous UK’s Crystal Palace, a huge glass hall where colonial exhibitions were organised in the 19th century.

Crystal is also related to extraction of minerals, so we come back to diamonds.

I like the different layers in the work, which allows us to talk about different periods of history, different temporalities. The sound aspect also has a different temporality: the mix of traditional music with synthesizers bring us to more futuristic soundscapes. So the artwork can be placed in different temporalities, it allows people to authentic discussions.

An invitation to come closer

To round up, what does the title of the exhibition, COME CLOSER, mean to you?

I like the title in the sense that some of my way of operating, is making the distance shorter to improve communication. Somehow I like to think in terms of cultural planetarily, not globally, how closer we are to each other than we expect to be.

That what pulls us apart, what creates distance, is not the geographical distance between the borders, but it’s the ignorance. It’s not recognizing the existence of the other, not recognizing how we’re linked in many aspects of our own existence. How do we affect each other in the place that we share? For the moment we live in, in terms of ecology and wars and so on, we have to be aware of how close we really are.

So it’s a statement to invite people to even come closer. Not only the physical act of putting two bodies together, it’s also inviting people to understand how common our history is, and the place we share.

Coming closer is an act of trusting too. Even if during our performances, constructing our towers, I would not advise you to come closer unless you use boots and helmets. Maybe here you need some distance. (laughs) But we will bring people closer through sound, and through storytelling. And the structures are big enough for people to feel part of it.

And eventually, when the structures are finished, the audience will be able to come closer.

Yes, at a second stage of the work. Then the audience will become the performers too.

Thank you very much.

Interview by Pieter Boons, 04.04.2024